What is Podiatry and what do you do?

I agreed to speak with Paul Welford, one of my Physiotherapy colleagues who was interviewing the multiple disciplines that work at Pure Sports Medicine (PSM).

Paul was looking at the various skill sets that operate in the organisation and what areas were clinicians working in outside of PSM.

Paul had a list of questions that he wanted to discuss for this article and these are on bold within the text, my responses are below the bold text.

What are your own activities outside of PSM?

Mark: Since I stopped playing football, I have built up my biking. My personal goals are to maintain 100 runs and 200 rides every year. For various reasons this year, my running has taken a back seat and I have spent more time on the bike.

I use Speedplay cleats and I’m actually on my third cycling shoe for this year. I’ve picked up a new set of Giros which are nice – quite old school – but I do need to be reminded by my more snobbish cycling friends to buy something new every once in a while.

Where do you work when you are not at PSM, I know you work up at Birmingham City, but are you based across any other sites?

I am based in London for 2 days a week and I have been with Birmingham City for nine seasons now.

My practice is mainly musculoskeletal, biomechanics and gait analysis.

The difference with professional footballers is they actually have time for strength and conditioning; the things that make them less dependent on the orthotics that we tend to use with civilian patients. It’s a real culture shift. I think it defines what we do at PSM as well. We know from professional athletes that, if you are willing to put the time in, you can really minimise your structural risk factors by being strong or being long in certain muscle groups.

At PSM, our patients have work and family commitments – reasons why they can’t always invest the time that a professional sports person would. I really enjoy working in football. I screen for Wolverhampton Wanderers, see their injured players and also teach on the FA Masters module as St. George’s Park.

I am also based at 2 private hospitals, one in Birmingham and one in Leamington Spa as well as a couple of Physiotherapy units in the West Midlands which provided great variety over the working week.

So Mark. How does your work at Birmingham City look on the ground. Do you screen the players routinely, or do they just come to you with injuries?

Mark; At the start of the season we screen the new players. In addition to the Functional Movement Screen that all players will go through, I do a foot and ankle specific one.

This includes ankle joint flexibility and, bizarrely, players’ foot shape and size just to ensure that they are wearing an appropriate boot. You might be surprised at how many players are wearing boots that just aren’t the right fit.

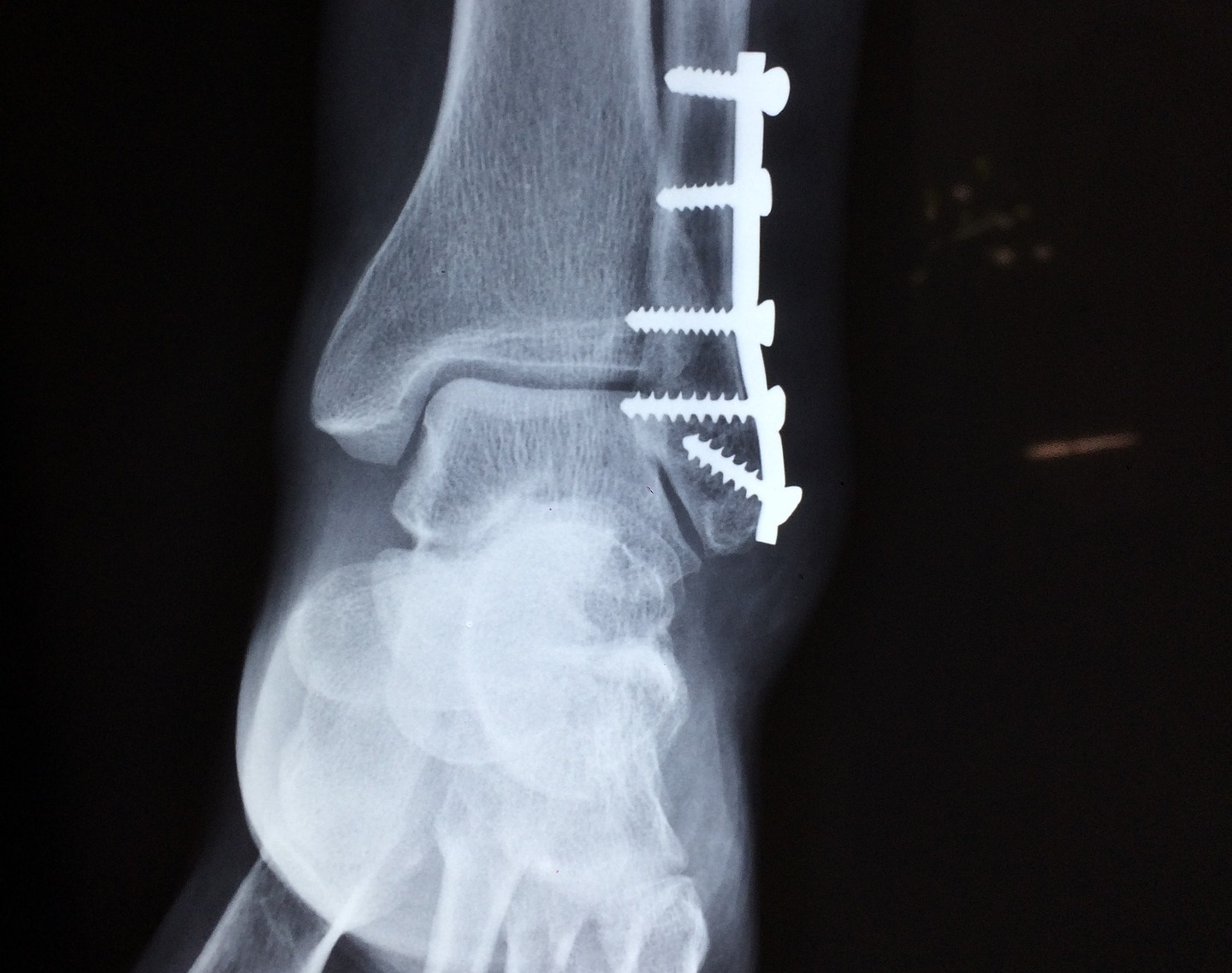

As well as the boot’s shape, it can be the stud distribution that just isn’t right for the player. For example they may have previously had a fracture at the base of the fifth metatarsal.

There are certain boot styles and trainers that suit certain conditions and foot types better than others. I work with the team to get them stronger, minimise their risk factors and work out what role their footwear might play. That’s where the multidisciplinary (MDT ) approach really helps.

Mark, you must see a lot of football players with ankle sprains? If they have structural instability, what is your advice to them? Do any of them use ankle braces or do you prefer taping? At what stage would you consider surgery?

We tend to use taping a lot for ankle instability in football.

Ankle bracing is rarely tolerated in a professional sporting environment, although we have used it with England netball. Of course, both of these groups are also highly amenable to good ankle control programs. You beast them in terms of ankle proprioception as much as you can.

We have players that have a completely absent ATFL. The question is often whether the other two (ligaments) are doing their job properly. I have some great videos of positive anterior drawer tests. Sometimes I just think ‘how can that ankle perform?’. But if you secure them with tape and give them as much control as possible, life becomes manageable.

When would I refer them for surgery? If they get reactive oedema after every training session with pain (of 4−5/10) that limits their next training session then you have to consider the value of allowing them to continue.

We can probably keep them stable within reason, but really at this point you should refer them on. Often you can time their surgery in the off-season, in the interest of keeping them playing. So I would say that, as much as you want three ligaments on the outside of your ankle, you can often manage with two.

Now to your work at PSM. What is your approach to assessing a patient?

Mark: The framework that I use is the foot posture index — but assessing a patient standing with two feet on the ground is just the starting point.

I think that basing assumptions on how a patient moves from watching them standing is of limited value. I move from double limb support to single limb support to see what their ankle control is like.

I look at how hard they are working their intrinsic and extrinsic muscles in order to stabilise the ankle. Then I look at single-leg squat, probably in the same way that you do, but my focus is more on what happens to the foot position.

The two main parts of the foot that I assess are the rearfoot position and the navicular height. If you see a real loss of rearfoot position and a drop in the navicular, you can be fairly sure that there is a rotational component to their symptoms. At that point I get the patient walking, then running on the treadmill, to see how it all fits together.

When I read referral letters, I often see, “the patient stands with a moderate degree of pronation”. If you screen for mechanical risk factors with two feet on the ground then you are missing a big part of the problem because most patients don’t get symptoms in a standing position; symptoms come on when they move.

It’s fundamentally important to allow them to move at their own pace and to mimic their sport or provocative activity as best you can.

At conferences I often see reps marketing those technical and expensive looking pressure systems. What are your views on these and do they form part of your assessment?

Mark: Rarely do they form part of my assessment.

When I was at University Hospital Birmingham I held a monthly clinic where we saw non-responsive mechanical patients in a dedicated Gait Laboratory.

When patients walk through your door with having had multiple things inside their footwear, you have to try and make sense of it. I think pressure systems have a role to play for certain conditions but when I teach on the FA Masters module, I do a session called ‘Technology: Essential or Excess?’ which focuses exactly on this area.

Regardless of the systems that we use, as clinicians we still need to interpret that information. Pressure systems are objective measures, but won’t necessary tell you what the problem is.

I see a lot of clinicians hiding behind technology. Sometimes patients bring me reams of information. I’ve been doing this for 25 years and there are still times when I have to say, “I have no idea what this data is telling me or if it is adding any value to their clinical assessment.”

How important is footwear for the lower limb patients that you see at PSM?

Mark: Show me the person who wouldn’t benefit from shock absorbency being improved at the foot level. Of course, the body can absorb impact but footwear can help to moderate that impact force.

I also think that, at times, footwear can be overly-engineered. Footwear is maybe 20% of the equation. The question for the patient is, “do I want to do anything beyond the benefit I can get from optimal footwear? Do I want to commit to a strength and conditioning program to maximise my potential?”

Every patient who walks through my door will gain insight into the role of footwear, but rarely is it a complete solution. I think that footwear can be the reason that things can just drag on. It’s not going to be a game changer 7 times out of 10.

One of the most common questions that I get asked by runners is, “what is the best trainer for me?” Unless you have a criteria that allows you to answer this, you’re clutching at straws.

If your assessment reveals a significant rotational component, you might favour stability or motion control features in footwear.

I also look at ankle flexibility – I usually measure tibial inclination using an app. If a patient lacks ankle flexibility, this gives you insight into what the heel-height profile needs to be on their trainer. Someone with a stiff ankle who wears a minimalist shoe – that’s not going to be a good combination.

I think that this approach allows you to make well-informed recommendations on what each patient’s optimal footwear choice may be.

This usually allows for around 5 or 6 varieties of trainers that a patient can try. I think that at this point, comfort is important. Forcing someone to wear a trainer that doesn’t feel comfortable is going to cause problems.

Mark, what are your views on minimalist footwear?

Mark: For me, footwear choice is important to a point, but how and where you land on your foot is more important. I place my runners in 2 camps. If you are heel dominant, you are going to generate a higher impact force – a higher ‘bone burden’ on the shin, the knee and the lower back. If you land on the front part of your foot, there’s a bigger eccentric demand on the calf muscle group and therefore a bigger soft tissue component to their injury risk.

But if you look at the structure of the foot, where is the biggest bone? Well, it’s the heel; the metatarsals are not designed to take impact force in the same way that the heel is.

So the best of both worlds theoretically becomes midfoot landing. When I have this discussion with my (forefoot) runners, I have to respect that this is something that they have taken on board in making this transition.

I think that the patients that I see often don’t make the transition over a long enough period of time – it can be a real shock to the system. I think that if you are going to evolve from a rearfoot to a forefoot strike, you have to do the strength and conditioning work required to allow these body to deal with these new loading patterns.

My question to the patient would be, “what are you trying to achieve from this?”

I think you make the change for one of two reasons; either to reduce your injury risk or to improve your performance. Rarely does it do either. Personally, I just see a different pattern of injury – more Achilles tendon stuff and metatarsal stress fractures; this makes them unable to train as hard over the short to medium term.

Don’t get me wrong, there are people out there who have made the transition – but if you are changing to forefoot strike as a first-line treatment, we have probably missed an opportunity to change something with less mechanical cost.

At PSM I would occasionally get parents asking me to assess their kids who walk on their toes? Is there a particular point by which children really should be walking with a heel-toe gait? What should we say to parents?

Mark: Yes, it’s presentation I see a decent amount of. I think that if there isn’t a physical restriction to that child getting their heel to the ground then they should be using it.

The dilemma is that for most of the patients we pick up, it’s a real habitual pattern. So a lot of it is gait re-education – this is something that I think I have undervalued historically for a number of reasons.

When faced with that patient group, telling both patient and parent that there’s no structural reason why that heel can’t reach the ground, it may be that we start looking at footwear with a higher heel height, just to get that initial engagement.

Before you start getting them into barefoot heel contact, there has to be some feedback. This tells them “my heel’s on the ground; I’m safe, I’m happy”. Then we can start transferring this outside of footwear.

Now for some questions on foot and ankle surgery. What are your views on hallux valgus correction?

Mark: These are the criteria that I use: What is the size of the deformity? What is the degree of structural shift? What level of pain is the patient experiencing and what impact is it having on their day-to-day life?

There is a staging system for hallux valgus. Generally we pick people up at stage two or three; stage three is the point at which most surgeons will say, “ok, that’s a decent deviation.” That ticks the first box, but if their pain is only 1 or 2⁄10 and it doesn’t bother them in day-to-day life then I’d advise against surgery. There’s life in that joint.

It’s only when you start getting above 4-5⁄10 consistently and it’s starting to affect sport or walking that I’d think about asking my surgical colleagues to give an opinion.

And what about hallux rigidus/ osteoarthritis in the first metatarsophalangeal joint?

Mark: I’ve been working with footwear companies for six or seven years now, looking at shoe stiffness — how much the shoe bends during walking – trying to reduce the dorsiflexion moment through the hallux.

I think that if you get these patients in stiffer shoes, life becomes a lot easier. We can’t give them any motion back, but we can reduce the need for the joint to bend in the first place.

The dilemma with using a stiffer outsole is that the shoes needs to have the classic rocker-shaped bottom. You show me the person who wants to live in stiff, rounded trainers. So really, there are conservative tools that we can use, but our ability to use them is limited. If they are stiff – painfully stiff – then they might need an orthopaedic opinion.

Is there anything that you would want orthopaedic colleagues to know, from your experiences in podiatry – anything that you think could perhaps be done differently?

Mark: I think that my orthopaedic colleagues know that by the time my referral gets to their door, I’ve explored all the conservative stuff.

Generally I’m looking for the solution that gives the best outcome for the patient in the shortest amount of time, and I try to be really honest with the patient about that – so I refer my patients to orthopaedic teams that follow the same kind of approach.

We talk a lot about what happens to our patients’ biomechanics following surgery. It’s really reassuring to know that there are surgeons out there that really try and think about a patient’s life beyond their surgery.

It’s not just a six-month follow up, it’s what might happen 12 months or two years later. Those are the type of surgeons that I like to work with. Someone who recognises that, at some point, their patient has to walk out of the door.

Plantar fasciitis/ plantar fasciopathy, or whatever it’s current name is? What is your approach to treatment?

Mark: It’s the commonest condition that I see.

My Masters thesis was on : ‘Injection techniques in chronic heel pain’, back in 2000.

At the time, I was working with the rheumatology team, chasing patients around the room with a 23-gauge needle and syringe while thinking, “there’s got to be a better way of doing this”.

During my research I came across an ankle block injection technique – it’s like when you go to the dentist really, a local anaesthetic. An ankle block allows you to block the tibial nerve at the ankle level, making the heel go numb in less than 20 minutes. Then you can put the needle into patient’s heel without having to chase them up the bed.

So then I would inject things like saline and local anaesthetic into the plantar fascia origin, getting decent outcomes at times.

I think my biggest criticism in the management of plantar fasciitis is the stop-start approach that it follows. I don’t think that there is one single thing that is going to solve it, its a combination of key factors.

If we are going to treat this, we need to ensure that we are reducing the mechanical load, because every single step causes stress-strain in the tissues. That’s why most foot and ankle conditions drag on, but especially plantar fasciitis. So, unless you are de-loading that structure and giving it a chance to recover, then all the other modalities will have limited impact.

It is a frustrating condition to have and can be frustrating to treat, but I think that it helps to do the right things at the right times.

Be very aggressive in offloading the plantar fascia during the first six weeks. Whether you choose to use taping, or something else; be consistent. Emphasise to the patient that just using a tick-box approach is not enough. Especially as by the time patients walk through our door, they have often already had the condition for six months.

Use the sports doctors at PSM. Try to use shockwave as a means of stimulating tissue activity – try to get some tissue repair going on, alongside the mechanical offload. So in summary: mechanical offload, tissue repair and try to keep the momentum the treatment program.

Finally, when you fit a patient with orthoses – are you fitting them as a temporising measure, with a view to removing them later, or is it, in some patients, something that you envisage them using lifelong. How do you approach that discussion?

It is dependant on the causative factor for the injury or symptoms.

Residual symptoms post injury with no previous symptoms prior to that injury, that may be an example of a short term strategy with orthoses. The time frame for orthotic use in these cases is also influenced by patients being committed to strength and conditioning post injury, giving the injured tissues an ability to deal with the mechical stresses they are expected to carry.

A larger group of orthotic candidates are those with obvious underlying structural risk factors such as foot position which drive higher mechanical loads into specific structures. This is the longer term orthotic users and the timeframe for using orthoses is always discussed during our consultation sessions.

Mark, do you have any tips for your colleagues when making referrals?

I would say that the further you go away from the foot and ankle, the less likely I am to make an impact. An exception to this rule would be when someone has an obvious leg-length difference and lower back pain. Do think seriously about referring your patient if things aren’t going the way you expect.

An example would be a patient with patella femoral pain (knee pain) who is six-eight weeks into a program. You would expect them to be 30 – 50% improved by this point; if they aren’t following this time line, think about getting Podiatry involved.

Equally, try not to make it a surprise for the patient. It helps to set the scene early on – tell the patient that their foot position could be linked to their knee-loading pattern. If the patient’s proximal control isn’t great then of course we need to address this through physio, but if things aren’t going the way you expected then consider Podiatry, the foot position might turn out to be that fly in the ointment.

Mark Gallagher

Podiatrist (Musculoskeletal & Trauma)

clinic@podiatricrx.co.uk

mark.gallagher@puresportsmed.com

Tagged as: Birmingham, Foot and ankle, Football injury, Heel pain, Leamington Spa, London, Podiatrist, Sports Injuries, Stratford on Avon

Share this post: